On April 21-22, Undark’s senior editor and a KSJ fellow will be featured at the annual Association of Health Care Journalists conference in Orlando.

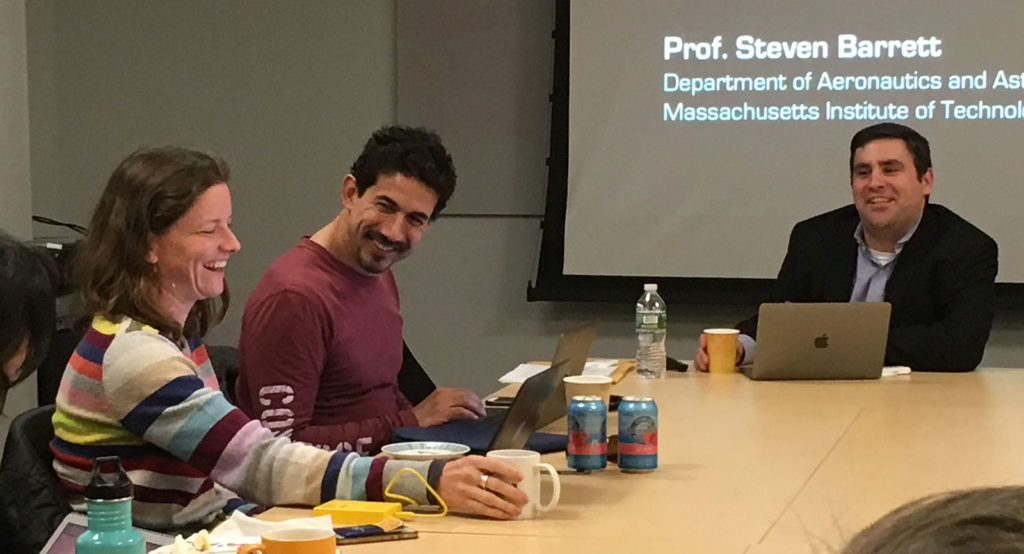

Climate Change: The View From 35,000 Feet

Steven Barrett of MIT tells the KSJ fellows that jets and their contrails could dash hopes of reversing global warming.

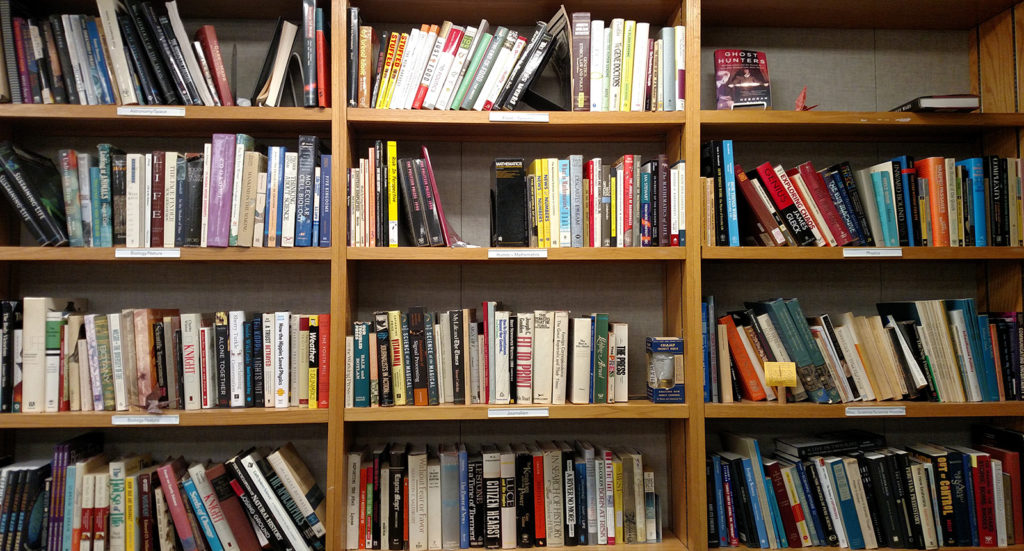

Author, Author, Author: Three Books From KSJ

Mark Wolverton, Meera Subramanian, and Maura O’Connor give practical advice about writing a book and getting it published.

Of fire and flat tires: The lives of KSJ fellows

To kick off their 2016-17 year, Knight Science Journalism fellows share stories from their careers — what they’ve learned and what they hope to take away.

Welcome 2016-’17 Fellows!

Another fellowship year got underway last week as 10 science journalists from around the globe arrived in Cambridge to begin a year of discovery and learning at MIT, Harvard, and beyond.

Calling All Science Journalists!

The application period for the 2016-17 Knight Science Journalism Fellowship program will open on January 1. Science journalists from around the world are encouraged to apply.

"

" "

" "

" "

" "

" "

"