“With every story, there is a story not being told.” That observation from STAT health and tech reporter Erin Brodwin, made during the Knight Science Journalism Program’s June 17th webinar on health care reporting, spoke to the importance of weighing a health policy’s potential benefits with its potential risks and harms. The comment also helped set the tone for an engaging panel discussion that went beyond the basics of health reporting to explore weighty topics like how to strike the right balance in a story, how to deal with misinformation and science hesitancy, and how to illuminate not just the “products” of science but the process.

The event marked the third in a series of webinars organized in conjunction with the release of KSJ’s digital Science Editing Handbook. Joining Brodwin on the panel were Carmel Shachar, Executive Director of the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School, and Atlantic staff writer Katherine Wu. (A recording of the webinar is available here.)

The panel was kicked off by Brodwin, who encouraged editors and reporters to look at health stories with a skeptical eye. From health care mergers to the deployment of health care algorithms, she said, there’s always an “overstory” — the rosy narrative found in press releases — and an “understory,” born of a careful, independent review of the evidence. It is the journalist’s job to connect and contrast the two, and fill in any gaps that might emerge, to tell a balanced story, she said. She encouraged reporters to ask themselves, “This thing that I am about to write, or not write about, does it weigh equally the risk of public harm with the risk of public benefit?”

Brodwin was followed by Shachar, a policy expert who offered insights from her years of experience working with health care reporters. Shachar, who has a background in both law and public health, advised reporters to take time to rigorously prepare for interviews, to conduct background research ahead of time, and to not shy away from asking follow up questions that delve deeper into essential ideas. Citing the recent example of vaccine hesitancy in the U.S., she cautioned journalists against dismissing people who don’t share their beliefs and views. Not only can it hurt the story, she said, it can steer science skeptics even further from facts and truth. “People are trying to weigh the risks and benefits to do right by their families and communities,” she said, arguing that this sentiment should be an important part of the narrative in any reporting on delicate health care topics.

Shachar emphasized that sometimes good policies do not work equally across all communities, and that competing narratives about a policy can shape the way the public understands it. She noted that in some of her earlier work with the Affordable Care Act, which expanded health coverage to millions of Americans, she found it important to ask “who this well-intentioned bill was leaving behind.”

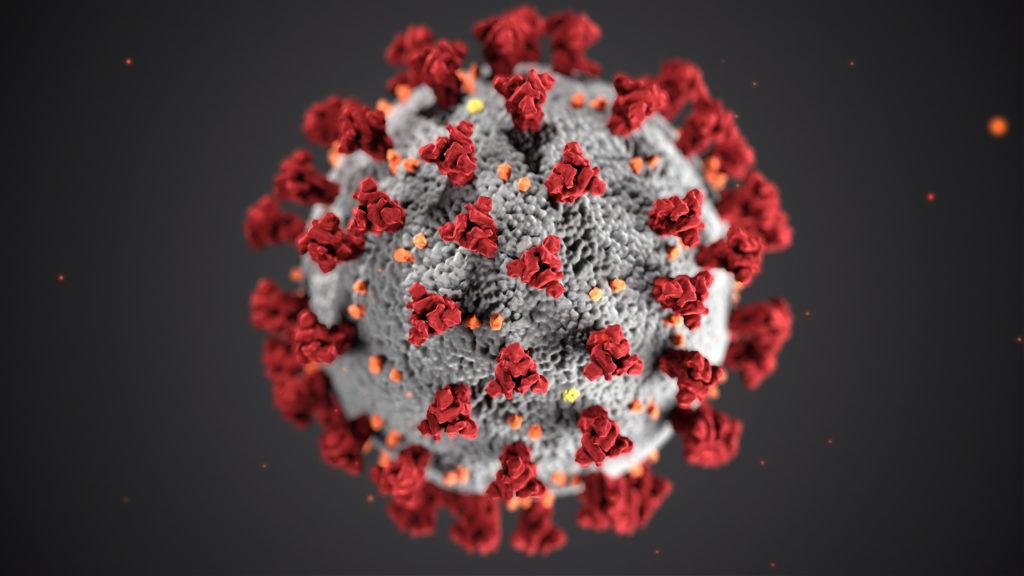

The panel’s final speaker, Wu, a scientist turned science journalist, spoke about her personal experience of reporting science “as it happens.” As a science journalist, she explained, she seeks not only to explain how the science behind a technology or discovery works but also to give readers an understanding of the process that led to it — an approach she says can be especially important when reporting on topics such as health care and infectious disease, where human lives may be at stake.

“Data gathering is this really iterative process,” said Wu. Talking about that process, she says, can help a reader make sense of the twists, turns, and revisions of science — such as the seemingly flip-flopping recommendations given by infectious disease experts when initial data was still being collected during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. If she can help readers better understand that “data is gathered by human beings who sometimes make mistakes or have their own biases,” she says, those readers may be better equipped to recognize misinformation and misrepresentation of data when they see it.

As the panelists’ presentations drew to a close, Wu spoke about the value of highlighting the people behind scientific discoveries, which she says can be a useful way to showcase the interplay between science, culture, and human behavior — and bring diverse perspectives into a story: “For a reader to see themselves reflected in a human being in a story can be just as salient as a quippy metaphor.”

Leave a Reply