Editor’s Note: This is part of a series of dispatches from the Knight Science Journalism Program’s 2020-21 Project Fellows.

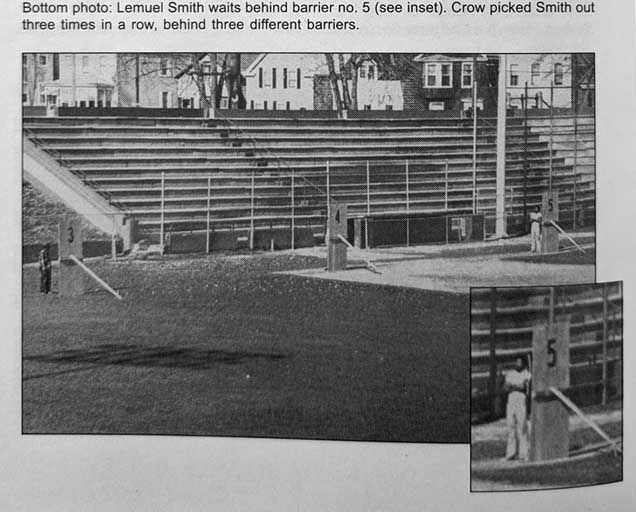

In 1977, a dog named Crow entered a stadium near Albany, New York. On the stadium’s playing field, five men stood behind large plywood barriers. Police had Crow sniff a bloodied cloth found at the scene of a murder, which contained a smear of the suspect’s feces. The dog then approached one man, Lemuel Smith, and urinated on his leg. This provided an identification. Even if that apparent match didn’t stand up in court, police reckoned that the dog could be used as leverage — to psychologically pressure Smith, now their chief suspect, and turn an accusation into a confession.

This was just one of the many cases I came across as a Knight Science Journalism Project Fellow researching dogs and the law. The account comes from Denis Foley’s book, “Lemuel Smith and the Compulsion to Kill,” which relies primarily on claims made by police and prosecutors, whose methods seemed questionable at times. (They were first tipped off by a psychic.) Smith was convicted. While incarcerated, he allegedly killed a corrections officer. His appeals effectively ended the death penalty in New York state, and he has been in solitary confinement ever since.

There are many things we don’t know. There are no searchable databases authoritatively tallying the number of cases involving canines, and few ways of knowing how often the courts use scent lineups similar to the one police used to identify Smith. Moreover, certifying organizations estimate that there are now some 15,000 active police dogs, in addition to countless civilian handlers who assist with investigations, but there’s almost no comprehensive data. Of course, the news is filled with stories about search and rescue dogs that find missing people, drug-sniffing dogs that turn up narcotics (or that generate probable cause for a search that turns up evidence), and patrol dogs that intimidate and subdue suspects. I also found criminal cases where testimony about a dog’s behavior was accepted as direct evidence of guilt in court. Which is to say, no direct physical evidence of a crime turned up, and yet jurors had been convinced that a trained animal sniffed out something that humans cannot perceive.

Was there really something where there appeared to be nothing?

In the course of reporting, I spoke with an olfactory neuroscientist who asked me to envision an alternative scenario: Imagine if a perfumer, or an aromatherapist, took the stand in court, and testified about matching a person’s odor to a physical piece of evidence left at the crime scene. Would the courts accept that expert, and would jurors believe a trained human who claimed he or she could match two olfactory clues to help solve a crime? We assume dogs live life through their noses, and there’s a vast cultural appreciation that these animals are social beings, unfailingly loyal companions. A human sniff witness wouldn’t fly, because many people accept the myth of poor human olfaction. Certainly, the anatomy of a canine reflects a far superior olfactory system?

But we seem to be selling ourselves short. In some instances, humans can outperform canines (most notably when it comes to detecting amyl acetate — one of the characteristic odors in bananas). People can apparently even follow scent trails outdoors.

When I brought up this research on a Zoom call late last fall, I hadn’t actually given much thought to which claim sounded more extraordinary. But I’ll concede: Scent-tracking students must have seemed even more unbelievable than crime-solving canines. Afterward, I decided to double check the review paper where I’d first read the reference, and I downloaded a study published in Nature Neuroscience, which included a supplemental video. In the video, a blindfolded woman, wearing knee pads and earmuffs (designed to limit non-olfactory sensory inputs), crawls on her hands and knees across a grassy campus lawn, her nose close to the ground. The scent trail extends several feet before angling off to the right. She briefly casts back and forth until finding the trail, which, the study says, was a dilute solution that smelled like chocolate.

A video showing a blindfolded woman sniffing a scent trail in a grassy campus. (Adapted from J. Porter et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2006.)

It seemed funny — in an odd, head-turning way. In thinking about why these long-held assumptions about olfaction remain, and in thinking about those who have been identified or incarcerated because of an odor, a type of evidence that appears to extend past the threshold of detection (and way past the limits of human imagination), the research doubled as a subtle incrimination of a much larger problem with common sense assertions that we assume are scientific. These cultural assumptions and biases help explain the paucity of data and accountability, and, at least to my mind, are all the more reason to do what science journalists do: Question everything, and find the limits of what we thought we knew to be true.

Peter Andrey Smith is a reporter who has covered science and medicine for The New York Times Magazine, Outside, Wired, and WNYC Radiolab, among other national outlets.

[…] alineaciones de olores similares a la que la policía utilizó para identificar a Smith», explicó. Por otra parte, Andrey Smith señala que las organizaciones certificadoras estiman que en la […]