“The Mennonites were my first real sponsors.”

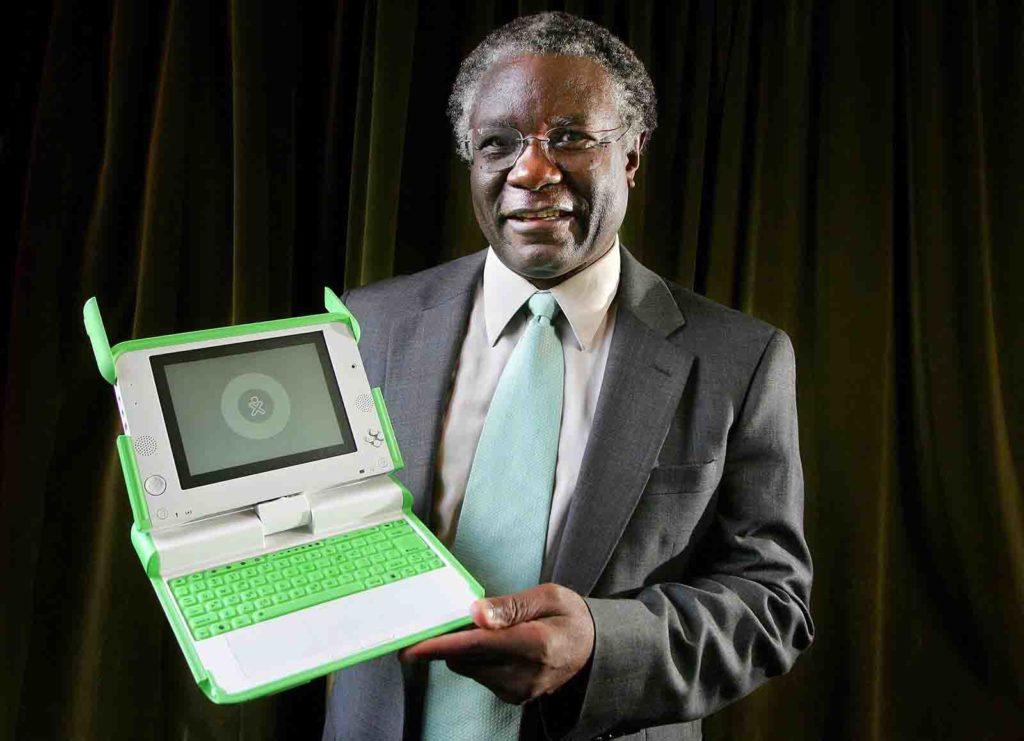

I interrupted my interview of Calestous Juma, professor of the practice of international development at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

I was writing a story that sought to understand the motivations of four young founders of policy think tanks in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Each had trained in Europe or the US, but returned home to establish institutions from scratch. Juma was among them and he remarked that his African Centre for Technology Studies in Kenya, had been partly funded by the Mennonite community of Nairobi.

“That’s like the Amish? Aren’t they supposed to be anti-technology,” I asked.

Not really, Juma replied. “They have a reputation for being against the modern world, but what they oppose is consumption; they value innovation and creativity.”

The response was a classic Calestous Juma response. It was pithy. It provided context. It displayed wit. It showed fairness to a misrepresented minority. It prompted the listener to pause and it forced me to think.

It came back to me in my shock over his untimely death on December 15th at the age of 64. And I found myself far from alone in my grief and dismay – or my wish to acknowledge the importance of his contributions.

“Tributes pour in for late Kenyan scholar Calestous Juma” was the straightforward headline from Al Jazeera. The magazine Quartz published an essay highlighting his support of innovation in Africa as “the gift he gave us all”.

But I want to pay tribute to another aspect of his generosity – his endless patience and openness with journalists seeking to understand his work. I’ve appreciated that for more than 20 years, since a day in the winter of 1995. I’d been assigned the UN science beat as a reporter on the staff of Nature and Juma was the newly-appointed head of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, which had just completed an important meeting in Indonesia.

I knew little then about the convention, nor about its impossible mandate to protect global biodiversity, without harming the ability of countries to become richer.

More to the point, it was late on a Sunday night. My copy was nowhere finished, and I could feel the shadow of my editor’s presence. These were the pre-Internet days when a deadline really was a deadline.

Somehow, I managed to locate the hotel where Juma was staying, picked up the phone and asked to be put through. He took the call and spent probably more than an hour patiently explaining the convention and its legal, political and scientific intricacies to one very grateful rookie correspondent.

He was inclusive before the word became mainstream. He genuinely liked people, especially students. He did not regard teaching as being inconvenient to his research ambitions. The classroom for Calestous was a laboratory for ideas, not necessary punishment on the way to a glittering academic research career.

And he was fearless in a way valued by journalists everywhere. He had strong opinions and did not hide them. He also had an ability to seek and find consensus—the ready supply of witty jokes helped him to cut through arguments and find solutions. He was an inveterate starter of initiatives for development in Africa and builder of institutions in Kenya. Perhaps, above all else, he was committed to the freedom to ask questions, to criticize, to publish. As a scholar of innovation, he knew well that there can be little innovation without the freedom to think.

***

Let me return again to that moment in 1995. It doesn’t seem that long ago but in the mid-1990s, Europe, Africa and the US were fighting a relatively minor cold war; this was a war to make international rules for the transfer of genetically modified organisms between countries, or “living” GMOs to be more precise.

Europe and Africa wanted strict rules and tough penalties on the grounds that such GMOs have biosecurity risks and may also be a risk to biodiversity. The US government, on the other hand, felt the concerns to be overplayed, arguing that harsh regulations would harm both trade and science.

As head of the UN convention, Juma was responsible for finding a way forward, to bang heads together. The result is today’s Cartagena Protocol. Some years later, he also persuaded pro and anti GMO experts and policymakers to sign up to a common framework in which to develop biotechnology among African Union countries.

Few, not least Juma himself, believed these agreements to be what everyone wanted. But he also understood the importance of give-and-take; that ‘winner-takes-all’ is not a recipe for well -functioning societies.

Juma always had an eye for big problems and I think it frustrated him that he couldn’t do more to fix them. So he used his position at Harvard both to mentor a new generation of innovators and try to improve understanding of why these questions mattered. His international development classes became a kind of finishing school for anyone wanting to work in, or research, international development.

I remember on another early visit to Boston in 1999 when I was working at New Scientist magazine. I dropped in at Juma’s office. He wasn’t there but I fell into conversation with another visitor whom Calestous had invited for a lecture tour of the US. This was Anil Gupta, the founder of the Honeybee Network, a non-profit founded in India that records and shares thousands of stories of how some of the world’s poorest people are innovating for themselves.

“People who are economically poor, are not poor in their minds,” Anil would later say in a TED talk. That is what Calestous wanted. He wanted Harvard, MIT and other elite schools in the US to hear Anil say: “Minds on the margins, are not marginal minds.”

***

Leaving Kenya in no way diminished Juma’s commitment to the nation of his birth, nor to the wider cause of African development.

Some years ago, he laid the foundations for the Victoria Institute of Science and Technology in Kenya. And towards the end of last month he wrote excitedly about establishing yet another new institution, the John and Clementina Institute of Science and Technology, in honour of his late mother who died in August.

“She believed that the best gift one can offer to a community is to give its children and youth better nutrition, healthcare, education and appreciation for the environment,” he wrote.

Throughout his life, Juma gave so much to so many, asking for little, if anything, in return. And he would have been genuinely touched by the mountain of tributes after his death. It behoves all of us, in particular the politicians, businesspeople, the academic institutions, the philanthropists and the journalists who sought his advice, to try and give something back.

Rest in peace, Calestous Juma. You counselled thousands and, through them, influenced many millions. I just hope we can do justice to those memories by helping to make your final vision a reality.

Ehsan Masood is a 2017-18 Knight Science Journalism Fellow at MIT and contributing editor of Research Fortnight, a London-based science policy magazine.

It is heart breaking. I cannot believe Calestous passed away so untimely. Africa and the world still needed his brilliant mind, his untiring inquisitiveness and strive for genuine people-oriented development. He was my mentor, my role model, when I started my own career in the UN system (UNEP) in the mid-90’s. I had spoken with him earlier this year about a book he wanted to write on biodiversity, to mark the 25th anniversary of the Biodiversity Convention. The book was supposed to be launched at the Africa Biodiversity Summit to be held in Egypt on 6 November 2018. May his soul rest in eternal peace.