The Media Lab professor spoke with KSJ fellows about her efforts to build AI that can predict seizures and tell us when we’re sliding into depression.

MIT Postdoc Edmond Awad, on the Moral Dilemmas of Self-Driving Cars

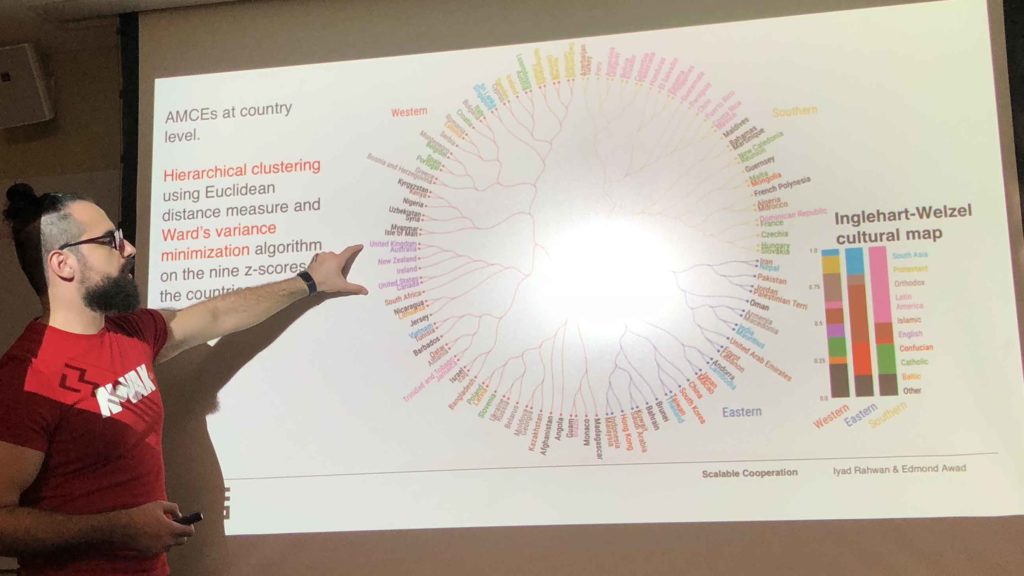

Awad and his MIT colleagues gave millions of people the self-driving-car trolley problem. In a recent visit to KSJ, he talked about what he learned. A self-driving car approaches a crosswalk and suddenly its brakes fail. It can avoid a person who’s crossing legally by swerving into the opposite lane, but then it will hit […]

Welcome 2016-’17 Fellows!

Another fellowship year got underway last week as 10 science journalists from around the globe arrived in Cambridge to begin a year of discovery and learning at MIT, Harvard, and beyond.

"

" "

" "

"