Despite the pain and disruption of the pandemic, the fellows have continued to pursue ambitious journalism projects since departing MIT.

They Don’t Just Fall Out of Trees: Three Science Writers on the Art of Finding Expert Sources

In a wide-ranging webinar, journalists Wudan Yan, Melinda Wenner Moyer, and Roxanne Khamsi shared insider tips for finding and vetting sources.

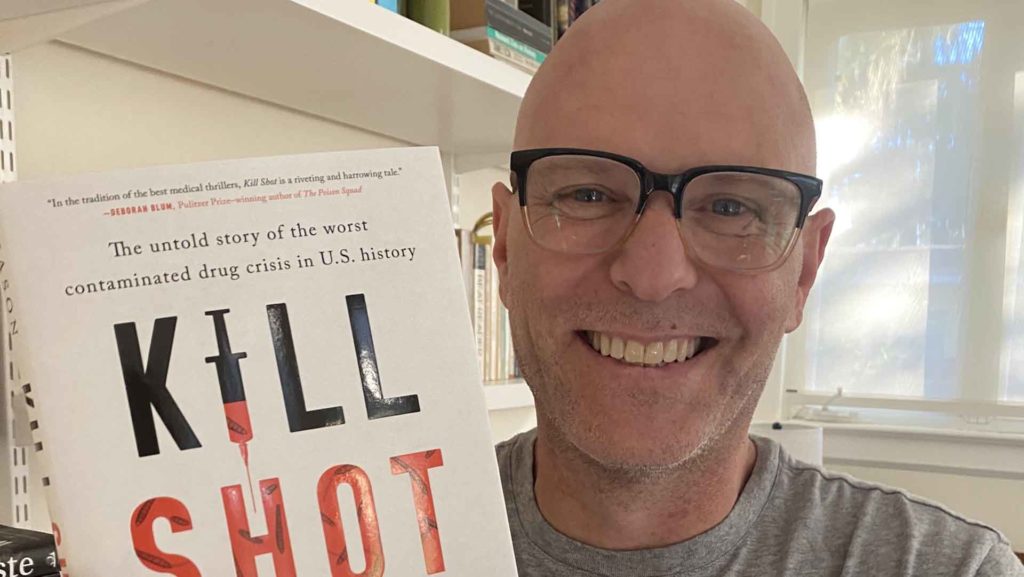

In ‘Kill Shot,’ Jason Dearen Takes Aim at a Medical Murder Mystery

The former KSJ fellow talks about the origins of his debut book, and the extensive reporting process that brought it to life.

"

" "

" "

"