Journalists Emily Anthes, Apoorva Mandavilli, and Ed Yong spoke about the structures and incentives that shape science — and how Covid-19 is changing them.

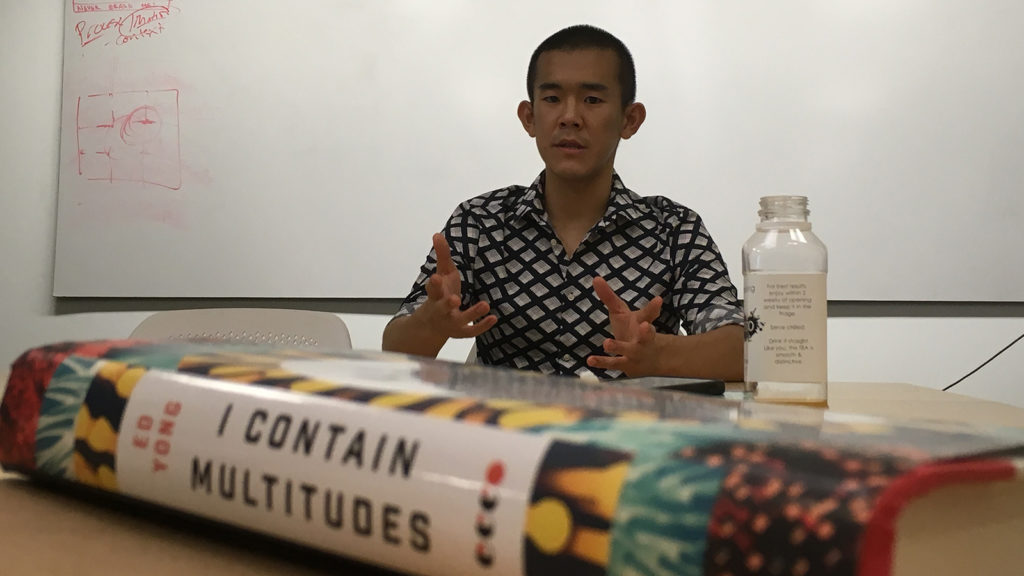

At KSJ, Ed Yong Talks About the Life Inside Us

The author’s new book outlines what we know — and what we do not know — about the bacteria that reside in, on, and around us.

"

" "

"