Forty years ago, as the Pioneer 10 space probe was leaving Neptune’s orbit and the first reports of HIV as a possible cause of AIDS were emerging, veteran journalist Victor K. McElheny launched what would soon become the world’s premier science journalism fellowship program.

Located on the campus of MIT, and in the heart of one of the planet’s most vibrant science and technology hubs, the Knight Science Journalism Program — originally known as the Vannevar Bush Fellowship — has flourished, nurturing the careers of some 400 science journalists who have spent time there as fellows. Some broadened their horizons, others discovered passions they never knew existed; all plunged into the deep waters of science and technology to emerge as more skilled storytellers.

On a chilly weekend in April, many of those former fellows returned to Cambridge to celebrate the program’s four decades of existence — an anniversary marked not just with cheerful reunions, toasts, and group photos, but with talks and panels featuring luminaries from the world of science journalism. More than 250 attendees packed the top floor of MIT’s Samberg Conference Center, overlooking the scenic Charles River, where they reflected on how far the field of science journalism has come, while grappling with several of the weighty questions it faces: How will the profession adapt to a rapidly changing landscape? What is its role in preserving democracy? What can be done to save local journalism? And, at a time when science journalists are becoming increasingly attuned to matters of social justice, how and when should race factor into our journalism?

Above all, it was a moment to celebrate a beacon of global science journalism — one that has helped writers, photographers, and multimedia journalists from more than 40 countries become sharper at their craft.

“For 40 years, the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT has stood for science journalism with integrity, has publicly supported it and many journalists, and reminds the world on a daily basis that science journalism makes a difference in our understanding of the world around us,” said Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and current KSJ director Deborah Blum. “And the impact of that cannot be understated.”

With her characteristic intelligence and humor, bestselling author Mary Roach kicked off the Saturday proceedings with a keynote on the “seven bad habits of highly effective science writing.” Among her nuggets of “bad” advice: Get in over your head (“The struggle to try to understand a scientist’s research is often a way to include the reader and say ‘Let’s figure it out together’”); litter your prose with scientific jargon (“We are told to avoid scientific jargon but sometimes it is part of the story”); and profile people of no obvious importance (“The passion of some researchers who are not usually interviewed is sometimes very inspiring”).

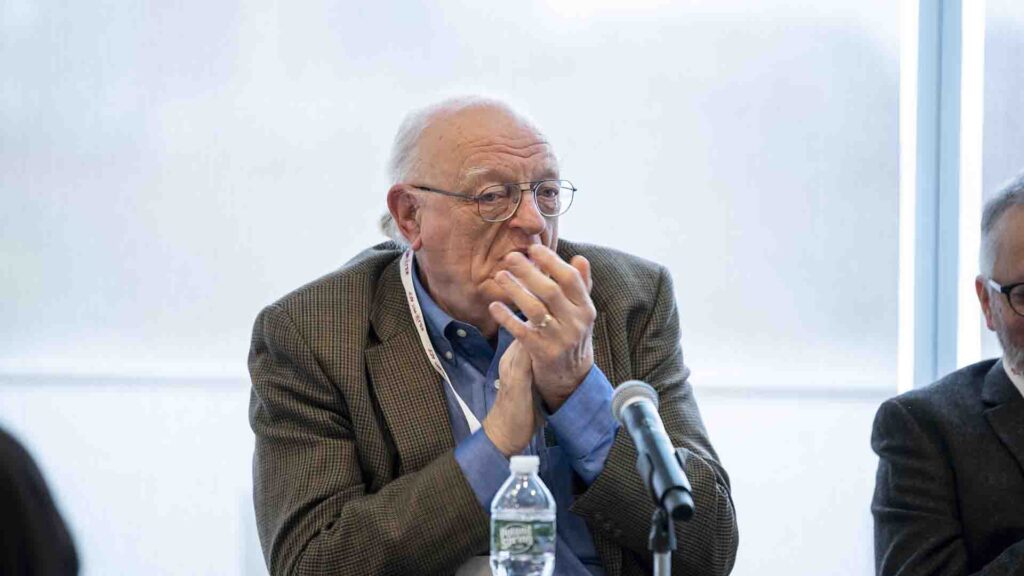

Boyce Rensberger, who directed the KSJ program from 1998 to 2008, took the podium next, shifting the conversation to existential questions about the future of science journalism. “We’re dealing now with a huge explosion of scientific information and websites that are not necessarily journalistic or necessarily independent,” said the former Washington Post and New York Times journalist. “It’s a new kind of PR — PR 2.0 — that goes directly to the public, without intermediaries.”

Rensberger noted that in the past, science journalists liked to think of themselves as gatekeepers — curators who selected and let through information that was important, fair, reliable. But now, not only are there no gates, he said, there are no fences. “Institutions, corporations and all those who want to influence public opinion go directly to their audiences. The sources are now in control of the message. And that’s scary.”

What does it mean for science journalism?

An international panel of former KSJ fellows wrestled with that question in the morning’s second session. Ehsan Masood, editor at Nature and a member of the 2018 KSJ class, told attendees that China’s growing investment in R&D is positioning that country to become a global research leader but that lack of transparency – it is still almost impossible to talk to Chinese researchers without official authorization – means that covering such increasingly influential research is posing new challenges for journalists.

Current KSJ fellow and freelance journalist Mary-Rose Abraham noted that in India, the world’s largest democracy, journalism has been hampered by sensationalism, misinformation, and a lack of access to reliable data. “The main challenge facing journalism in India is press freedom,” she said. “Any criticism of the government is considered anti-nationalist.”

“For 40 years, the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT has stood for science journalism with integrity.”

KSJ Director Deborah Blum

It wasn’t all bad news. In many African nations, said Akin Jimoh, editor of Nature Africa and member of KSJ’s 2001 fellowship class, science journalism is growing rapidly, despite continued government support for pseudoscience.

Indeed, national associations and international federations of science journalists have matured and become more active in recent decades. Many editors have realized the importance of multilingual journalism, the value of recruiting contributors in the Global South, and the potential for exploring stories that cross borders and go beyond the bubble of English-speaking journalism.

Those kinds of ambitious projects are expensive, noted Brazilian science journalist Thiago Medaglia, a member of the KSJ class of 2020 who spoke about the challenges of producing “Aquazonia,” a special report on how human activities are impacting rivers, lakes, and floodplains in the Amazon rainforest. “But it’s worth it.”

Closing the panel, 2008 fellow and New York Times staffer Pam Belluck talked about how science and medical coverage has been evolving at the newspaper of record. “We used to have to use euphemisms like ‘private parts.’ Editors seemed to be especially uncomfortable when a story involved the female anatomy. In recent years there has been a greater openness.”

In a lunch keynote, Margaret Sullivan — whose decades long journalism career has taken her from the Buffalo News to the New York Times and Washington Post, and now to The Guardian — led with a question: Can Journalism Save Democracy? Her answer: No, at least not by itself. “Different groups need to act,” she explained. “Journalists investigating, informed and engaged citizens taking that information and pressing for change, government officials willing to listen and to do their jobs.”

Moments later, the brand of serious, investigative reporting that Sullivan was championing was on full display when “Big Poultry,” a Charlotte Observer and Raleigh News & Observer investigation into harmful chicken farming practices, was honored with the 2023 Victor K. McElheny Award for local and regional science reporting during a luncheon ceremony.

“Journalists are essential to get the information across to the public in everyday language on all channels. A professional development program like KSJ builds the necessary skills and commitment.”

Founding KSJ Director Victor K. McElheny

In an afternoon session, KSJ associate director and 2016 Fellow Ashley Smart pulled the curtains back on a homegrown work of ambitious science journalism: The “Long Division” project, which was published by KSJ’s Undark magazine and chronicled the troubled, enduring legacy of race science.

“It was two years since the death of George Floyd at the hands of police officers in Minneapolis. And three years since The New York Times published ‘The 1619 Project’ that challenged Americans to reconsider the role of slavery in the country’s history,” Ashley Smart recalled of the moment he and Blum first began brainstorming the project. “Everyone was talking about race.”

Smart went on to describe how he, Blum, and Undark Editor-in-Chief Tom Zeller, a 2014 Fellow, brought together a team of leading journalists and editors to dissect the various ways that science has both perpetuated and been hindered by harmful ideas about race.

“Modern science was built on the racist science of the past. It’s impossible to think about these issues that remain so current without their connection to historical context,” said British journalist Angela Saini, one of four contributors to the Long Division project who spoke in the afternoon panel. That science of the past is still very much alive, she added. “There are politically motivated individuals within academia, white supremacists, who are still trying to push the idea that race has a biological value and that there is some sort of racial hierarchy.”

Hampshire College’s Alan Goodman and Yale University’s C. Brandon Ogbunu brought a scholarly perspective to the discussion, weighing in on some of the common traps that can ensnare journalists who cover race and controversies involving racism. Scientists have made missteps too, concluded panelist Jyoti Madhusoodanan, a 2021 KSJ project fellow who wrote for the Long Division project about how race has influenced breast cancer research. “Race has been embedded in scientific thinking since its inception,” she said. “Science sometimes ends up contributing to racial and health disparities. Our job as science journalists is to hold science accountable.”

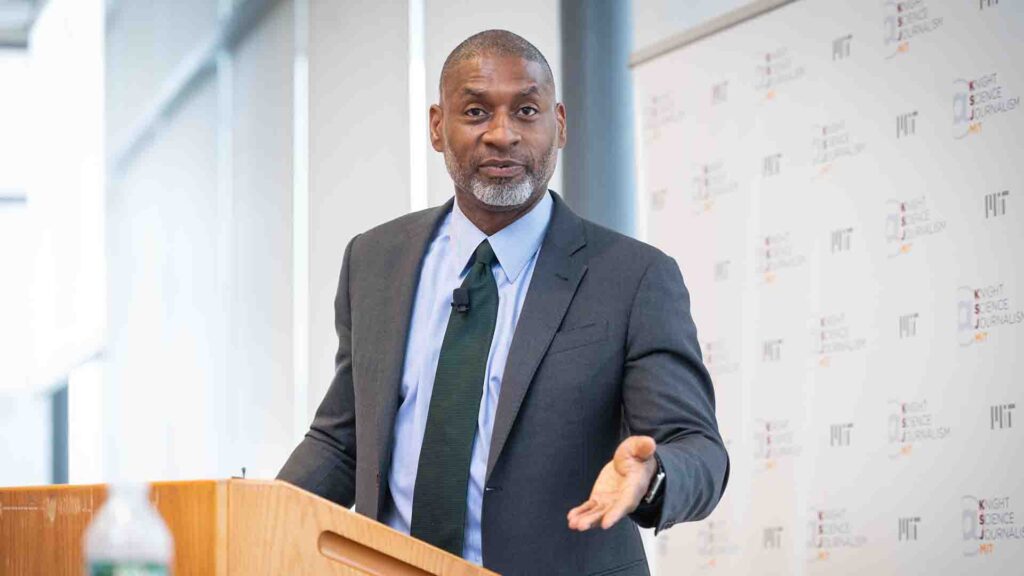

In the final talk of the day, Charles M. Blow, Op-Ed columnist at The New York Times, delivered an impassioned keynote, reminding us that racial myths have no relationship to the reality of human capacity. The racial worldview, he said, was invented. “Race is not a biological phenomenon but a social myth. It has created an enormous amount of human and social damage.”

After the two day celebration — which featured a Friday evening reception at the MIT Museum —alumni and guests departed Cambridge with a strengthened sense of community, reenergized to face what KSJ’s inaugural director, McElheny, described as a new era of science journalism in which the effects of innovation and discovery are constantly increasing. “Journalists are essential to get the information across to the public in everyday language on all channels,” said McElheny. “A professional development program like KSJ builds the necessary skills and commitment.”

KSJ’s Legacy: A Rich and Diverse Global Network

In April, former Knight Science Journalism Fellows traveled from as far as Latin America, Europe, and Africa to join in an anniversary that at times had the feel of a family reunion. For 40 years, the program has been not only helping to build better science journalists, but helping to build a supportive community. Here, some of the attendees share what it’s meant to them to have shared in that experience.

“The KSJ Fellowship was one of the most incredible experiences of my adult professional life. I was able to explore my curiosity deeply and broadly, surrounded by an amazing group of fellow journalists. I have no doubt that I am a better science journalist today because of it.”

— Cynthia Graber, KSJ class of 2013, and co-host of the Gastropod podcast

“After that year in the fellowship I felt much more confident as a professional, better prepared to face new challenges.”

— Caty Arévalo, KSJ class of 2014, and co-founder of EFEverde

“It provided me with a deep and supportive community of colleagues who helped me along the way. Journalism is an intense profession with a high burnout rate. The KSJ program is a necessary and important program because it keeps ambitious journalists in the profession and empowers them to reach new heights.”

— Jason Dearen, KSJ class of 2019, and AP investigative reporter

“Science’ is one of the few parts of society the public still trusts. Perhaps not each finding, but science in general. By encouraging excellence in science journalism, the KSJ program helps reinforce that trust. Nearly 30 years after my fellowship I remain challenged in all I write to honor that commitment.”

— David Ropeik, KSJ class of 95, author

“It’s not an exaggeration to say the Knight fellowship changed my life. By way of the classes and hackathons I attended in Cambridge, I discovered there was a whole world at the intersection of coding, design and science journalism. I realized newsrooms needed people with these skills and I started honing them.”

— Aleszu Bajak, KSJ class of 2014, and director of data visualization, Urban Institute

“I left MIT more connected to science, more brave about venturing into subjects and labs and about using tools of the physical and software kind. And more able to tune my senses when interacting with scientists… I left the fellowship taller in oh so many ways. And I was and still am pretty short physically.”

— Vivien Marx, KSJ class of 1998, and editor at Nature Methods

“People who go into science, technology, health, or environmental journalism certainly don’t do it for the money or fame. They do it because of their passion for the material—and because of their conviction that the public needs to know what the wielders of scientific and industrial capital are up to… [Science] always needs explaining, defending, and dissecting. That’s our job, and that’s what KSJ is here to support.”

— Wade Roush, KSJ Acting Director, 2014-15

Federico Kukso, member of the KSJ class of 2016, is an independent science journalist from Argentina with more than 20 years of experience writing about science, culture and technology.

Iam journalist Iam looking for fully scholarship or job that concerns at journalism field in any country