Editor’s Note: This is part of a series of dispatches from the Knight Science Journalism Program’s 2021-22 Fellows.

I walked into the Colorado Springs resort building in April with a mask, a lukewarm cup of coffee, and low expectations. It had been two and a half years since I’d attended an in-person conference, and in that time, I’d changed almost as much as the world had. I’d moved across the country, written a book, and had a baby. So I wasn’t sure what to expect when I entered the 37th Space Symposium.

The ballroom full of people in military dress uniforms was nothing too unusual—I’d gotten used to that since moving to Colorado Springs—but it was still jarring to listen to a speech in three dimensional space, with other people, and then sit down across from a four-star general willing to take my questions.

I was there to see Gen. John W. Raymond, chief of space operations for the U.S. Space Force, the military’s newest branch. I live near three of its six bases, and my parents live next to a fourth; many of my friends and neighbors serve in the branch, where they are known as Space Force Guardians. So to me, the Space Force is very real, though to many of my fellow science writers it is best known as the butt of left-wing political jokes and the subject of a comedy show starring Steve Carrell.

At the conference, most of the other journalists who asked questions were focused on the war in Ukraine, and how the U.S. military was using space for “situational awareness,” a term from the military-industrial thesaurus that basically means information gathering. I was more interested in what Raymond had to say about satellites’ impact on the rest of us.

To military brass like Raymond, satellite constellations are both dangerous and wonderful.

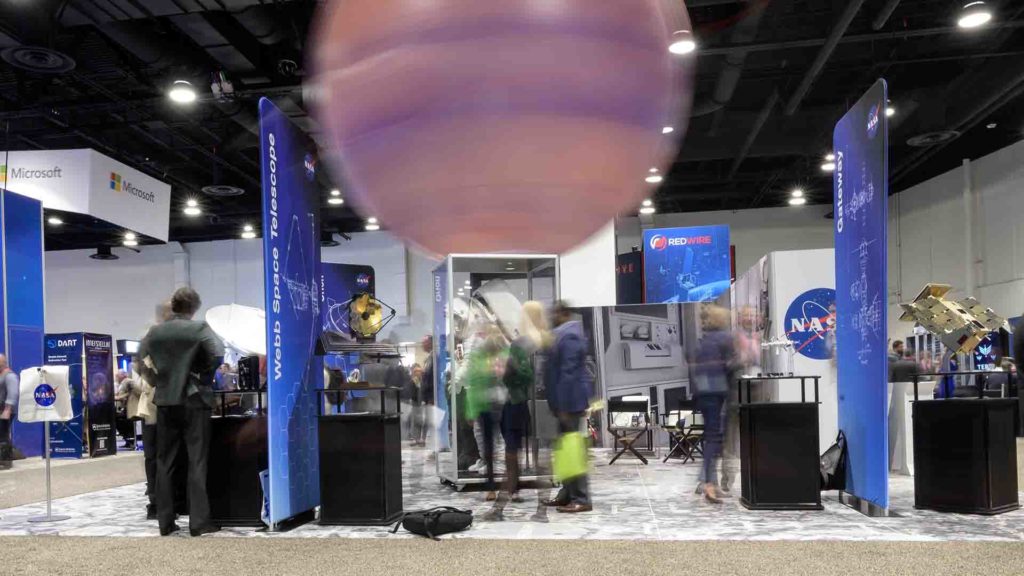

For the past few months, I have been reporting and researching about artificial light — work that I am doing as a Knight Science Journalism Project Fellow. Part of the story includes an increasingly large swarm of satellites in low-Earth orbit. Some of these take pictures of Earth, which the military and private companies can use. Others will eventually transmit internet connectivity around the globe. SpaceX is launching and operating most of these satellites so far, but companies like Amazon and others will join them soon, which means the space environment close to Earth is going to be filled with stuff. Much of this stuff, crucially, can affect the natural night sky that astronomers study, and that we all inherited from our forebears. But the satellites will also provide modern communications networks for people who otherwise couldn’t access them, including Indigenous groups, people in the global south, and even members of my own family.

To military brass like Raymond, satellite constellations are both dangerous and wonderful. Dangerous because they can collide, causing an avalanche of space debris that could threaten other assets, like military satellites. Wonderful because some of these swarms, like Earth-imaging constellations, are inherently safer than single satellites. Taking out American reconnaissance birds (more Pentagon thesaurus) will be much harder for Russia and China when the birds’ views are distributed across multiple small spacecraft, instead of one or two big ones. Raymond used words like “resiliency” to describe what these satellites can do for the military. I came away from his discussion with a sense that I had picked up on something new and important, which I now need to share with others. That sense of discovery has animated my entire fellowship and my previous research on this subject, which dates back more than a decade, but it felt tangible again in that hotel ballroom.

I expected to learn about satellites and the military that week. I didn’t expect this symposium to make me feel like I had finally re-entered the world. The pandemic, the demands of parenting young children, and the all-consuming work of writing a book had kept me cloistered since early 2020. Even my KSJ fellowship is remote. I have been alone with my family and my ideas the vast majority of the time since I moved to this Space Force-Air Force-Army city. The Space Symposium snapped me out of my isolation reverie. There’s so much to learn from simply chatting with people, rather than setting up pre-scheduled Zoom interviews. There are so many questions I haven’t even thought to ask. It just took some bland hotel coffee and a gracious four-star general to make me remember that.

Rebecca Boyle is an award-winning science journalist and author based in Colorado Springs, Colorado. She is a frequent contributor to Scientific American, Quanta, and The New York Times, and is a contributing writer at The Atlantic.

Leave a Reply