Editor’s Note: This is part of a series of dispatches from the Knight Science Journalism Program’s 2020-21 Project Fellows.

As a science journalist, I’ve spent a decade unpacking terms such as “benign ethnic neutropenia.” Avoiding jargon isn’t easy, partly because I love these words.

Split a word like neutropenia, and its roots trace ancient stories of how languages grew and people explored the world. As far back as the 14th century, Central American people turned to the heartwood of the campeche tree for a blood-red dye. Spanish ships returning to Europe loaded up on the timber to color fabrics. It was so precious that it became a prized target for pirates — a ship full of heartwood was equivalent to a year’s worth of any other cargo.

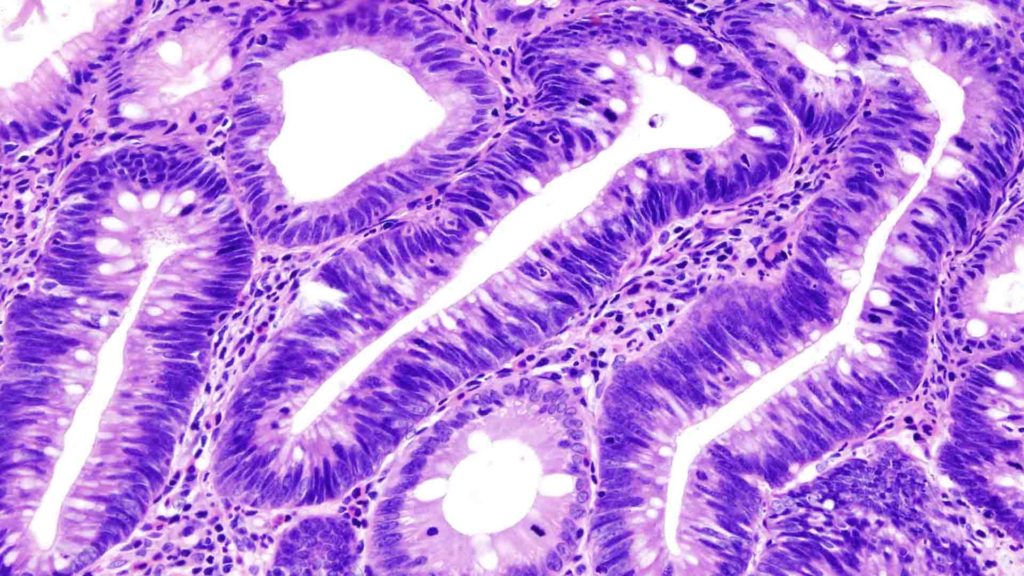

Five hundred years later, scientists began using the dye, along with another chemical, to study cells. Their technique, known as hematoxylin-eosin staining, is still used in pathology labs around the world. Stained with these dyes, acid-loving white blood cells turn a deep blue, and base-loving ones go red. Cells that aren’t attracted to either acids or bases, known as “neutrophils,” turn a salmon pink. Neutropenia’s suffix, penia, is rooted in a Greek word for dearth or poverty. Neutropenia, then, is a condition where pink-staining cells decrease in a person’s blood. And it’s a biological term that, without context or explanation, is just jargon. But to me, the word is a history and an adventure, a memory of color.

I’ve spent the last few months thinking about other words that are just as weighty but far more familiar — terms, such as “Black” and “Asian” and “White,” that most Americans have encountered at least once in their lives. Unlike neutropenia, these words are so common that we rarely stop to think about their complex origins.

The terms have been used in scientific research in a multitude of ways. For my Knight Science Journalism project fellowship this fall, I’ve been exploring their use in one arena: risk calculators that use a person’s weight, age, medical history, and other factors to estimate their odds of a heart attack, determine which diabetes medication they should take, or decide whether an expectant mother should have a second Cesarean section. Dozens of such calculators include a multiplier based on a person’s race or ethnicity.

Although race and ethnicity are social constructs, not biological ones, it’s tough to argue that they bear no connection to our health. After all, some of us are more susceptible to certain diseases than others. Across all kinds of cancer, Black patients in the U.S. are more likely to die of their disease than their White counterparts. South Asians comprise 25 percent of the world’s population, and 60 percent of its heart disease patients. “Benign ethnic neutropenia” is a real condition, where people of African and Arab descent tend to have lower levels of neutrophils. The condition is benign (as its name suggests), but it can mean people of these ethnicities get left out of clinical trials because their blood tests suggest they’re ill.

These differences in our biology and susceptibility to disease aren’t solely rooted in our genes. They stem from colonialism, ancestral immigrations, and our divergent present-day environments. But since this multitude of factors affect our health — and race, ethnicity, and ancestry are the simplest descriptors — researchers developing risk calculators have used terms such as “Black” or “Hispanic” as shorthand for our personal histories.

Multipliers and adjustments to calculators based on these terms are meant to account for the distinct health risks associated with different backgrounds. But they often backfire, because these simple words are a kind of jargon too.

Like the word neutropenia, they bear generations’ worth of meaning and memory. That baggage is lost when we reduce people’s ancestry and lived experience to the color of their skin. Consider Brown. When Harvard Medical School researcher Arjun Manrai’s mother visited her doctor’s office, she discovered that one race-based risk calculator they used didn’t accommodate her background as a woman of Indian origin. To get a more “accurate” measure of her kidney function, her doctor averaged the numbers for White and Black — potentially compromising her health and erasing her experience.

Black and white are words even a preschooler knows. But they can be just as complicated as any scientific jargon. In trying to understand their impact in clinical risk calculators, I’ve taken a step back from health risks to examine the terms we use to define race, ethnicity, and ancestry in science. How did these categories wind up in risk calculators? What harm or good have they done so far? What stories were lost when we reduced lifetimes to single words, and is there a better way to capture them?

Jyoti Madhusoodanan is an independent journalist based in Portland, Oregon. She writes about life sciences, health, STEM careers, and ethics for Nature, Science, The New York Times, NPR, and Discover, among others.

he problem with people who argue for inherent racial inferiority is not that they lie about the results of IQ tests, but that they are credulous about those tests and others like them when they shouldn’t be.