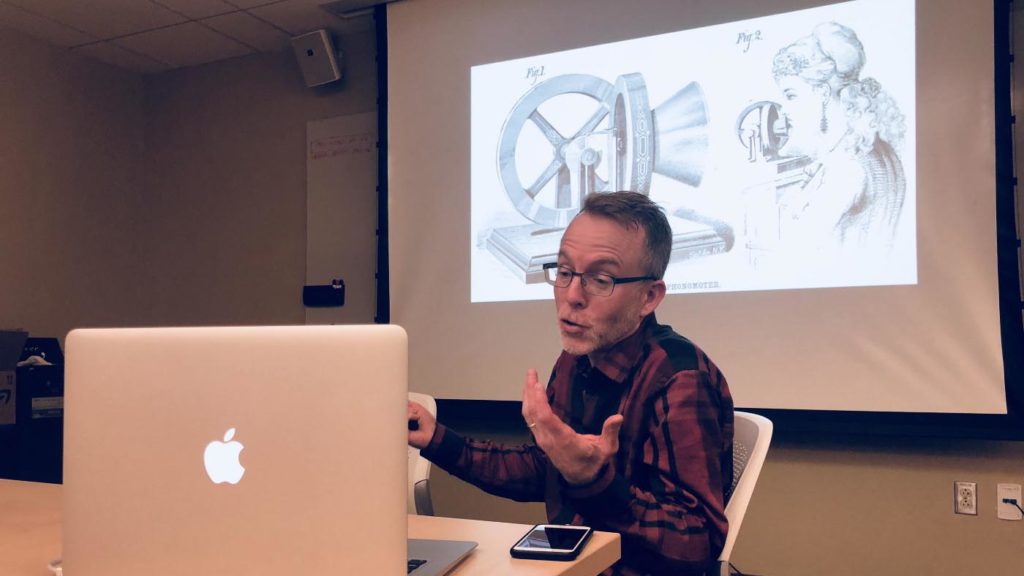

The longtime radio journalist took KSJ fellows behind the scenes of his book on the 19th century eclipse that drew a swarm of scientists to America’s western frontier.

David Baron’s first total solar eclipse sighting changed his life. “I was just seeing a sky I had never seen before,” he said of the February 1998 eclipse, which he watched from Aruba. As the moon passed in front of the Sun, blocking all of its light except for a “wreath of silvery thread,” he could see the planets in the backdrop. “I felt viscerally connected to the universe in all of its intensity.”

Speaking to KSJ fellows and guests last week, Baron described how the Aruba experience inspired him to become an eclipse chaser — and to write “American Eclipse,” a book that tells the story of scientists who trekked to the American West to observe the 1878 total eclipse. The book, Baron’s second, was published last year to coincide with the first total solar eclipse in the continental U.S. in 38 years.

Baron, a former KSJ fellow, said he decided early on that the last half of the 19th century would be an ideal setting for a narrative story. It was the golden age of eclipse expeditions, a time when “scientists were just starting to understand the nature of the Sun,” he said. He narrowed his focus to the 1878 eclipse because the path of totality, along which the Sun appears to be completely covered by the moon, went right through what was then the U.S.’s western frontier.

In his talk, Baron gave fellows a behind-the-scenes look at his dogged process for researching the book. He did much of the sleuthing at the Library of Congress and the National Archives in Washington, D.C., where he uncovered a trove of information, including drawings, correspondence, and even old train ticket receipts from scientists who had traveled west to perform experiments that could only be done during the eclipse.

In his talk, Baron gave fellows a behind-the-scenes look at his dogged process for researching the book. He did much of the sleuthing at the Library of Congress and the National Archives in Washington, D.C., where he uncovered a trove of information, including drawings, correspondence, and even old train ticket receipts from scientists who had traveled west to perform experiments that could only be done during the eclipse.

From a list of 70 potential characters, Baron ultimately settled on three: inventor Thomas Edison, Vassar College astronomer Maria Mitchell, and University of Michigan astronomer James Craig Watson. Baron says he chose those characters because they all had a lot on the line: Edison was testing out a new invention, the tasimeter, which he wanted to use to measure the temperature of the Sun’s corona. Mitchell had organized an all-female eclipse expedition — without the government funding that was available to many male scientists — at a time when many sought to exclude women from science. And Watson was searching for the elusive planet Vulcan, then thought to be the closest planet to the Sun.

Although the three scientists achieved mixed results, Baron thinks the eclipse was still a memorable event at an important time for America. “We had just come together as the country we know today,” he said.

Baron told the fellows that, even though some of the book’s main characters never actually met, their stories were connected — as were the stories of the thousands of other Americans who viewed the 1878 eclipse. All of them had come to the same place at the same time, he said. “They were all lined up on the path of totality.”

Leave a Reply