The 2017-18 KSJ fellows saved their best for last.

Their farewell month in Cambridge ended on May 25 with a graduation ceremony in MIT President L. Rafael Reif’s office, followed by a joyful if somewhat bittersweet dinner, hosted by Director Deborah Blum, Associate Director David Corcoran, and Program Administrator Bettina Urcuioli.

But it was the Showcase presentations on May 15 and 17 that put on display the curiosity, imagination, and resourcefulness that the fellows poured into their fellowship year – and their remarkable research projects.

“If you were pain czar, what would you do?” Rowan Jacobsen asked Teresa Carr about her research project, “Wicked Problems in Relieving Pain.” The answer isn’t simple, Teresa replied, because the U.S. health system’s approach to pain relief — which mostly boils down to “prescribe opioids” — has created a tangled web of abuse, addiction, finger-pointing, and more pain. But if she were czar, she said, she’d push for a multidisciplinary approach: behavioral and physical therapy, social support, research on alternatives to opioids — in short, “a better health care system than we have now.”

What Made China China?” asked Jane Qiu (left), in the title of her research project about the Proto-Silk Road — a network of prehistoric “superhighways” that connected East with West thousands of years before the Silk Road itself. Spurred by the taming of the horse and the invention of chariots, communities across Eurasia traveled long distances, exchanging goods, ideas, and genes along the way. Cultural and technological imports were crucial for the emergence of complex society in China, debunking the myth that Chinese civilization evolved in isolation from the rest of the world. The story of the Proto-Silk Road is a story of contact and assimilation. “It’s a story of shared humanity,” she said.

Joshua Hatch took us back to 1981 and a bold experiment in online journalism: The San Francisco Chronicle’s electronic edition, in which a user could read the text of any story by connecting a home computer to the Chron via a landline phone and a two-hole modem the size of a dictionary. Josh’s subject was “Augmented Reality and Journalism,” and his point was that AR is still in its 1981 stage: It’s out there, but we don’t know where it’s going. Today, he said, it has its uses — including image recognition and labeling objects in the real world (think of the Yelp Monocle) — but it’s still “experimental, expensive, slow, resource-intensive.” Even so, “newsrooms are starting to take notice,” and one day AR could prove to be much more than a gimmick.

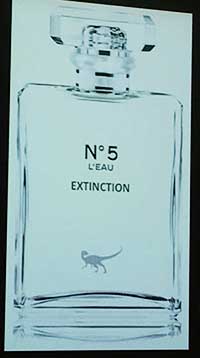

Conebush, scurfpea, hibiscadelphus … these are some of the “Ghost Flowers” Rowan Jacobsen has come to know over the past year. The author of books about oysters and apples, Rowan embedded with scientists at the local lab Ginkgo BioWorks on what seemed like a quixotic quest — to use genetic engineering to revive the scents of flowers gone extinct as long ago as 1806, perhaps to turn them into fragrances (right). In the process, he learned a lot about DNA, yeast, E. coli, enzymes, the aromatic compounds called sesquiterpenes — and the quintessentially quirky Harvard Herbarium, home to 5.5 million plant samples, including the dried-up but still viable flowers that Ginkgo is trying to sequence. “In some way,” Rowan said of the project, “we’re summoning the ghost of a lifeform, and we can receive communications from it.”

Sujata Gupta learned a lot, too — about researching, writing, and pitching science books for children aged 3 to 6. Over the year, in a process that included classes, workshops, and plenty of trial and error, Sujata produced two manuscripts for 32-page picture books — one about shadows, the other on climate change. One of her mentors, an editor at Scholastic Books, told her, “I know you want to get kids excited about STEM topics, but the important thing is creating a compelling narrative.” So in the shadow book, Sujata changed the character of the rock into an old woman — Tia Riya — and made the narrative compelling indeed. Here’s the ending (note spoiler alert): “She sat down, tired but happy. Her shadow danced with the other shadows. Together, Tia Riya and her shadow made a new home in that town. And new friends, too.”

“If you told me a year ago I would be talking about artificial intelligence in science journalism,” Mićo Tatalović said, “I’d have thought you were way off.” But he added that MIT gave him insights into the cutting edge of this technology, as well as the freedom and confidence to explore it during his fellowship. “AI and more general automation is here,” he continued, “and it’s coming to journalism as well,” in ever more ambitious applications — among them The Washington Post’s Heliograf, which claims to have published 850 stories in the past year, and The Los Angeles Times’ Quakebot, which alerts readers to earthquakes. (Including at least one embarrassing glitch: a news bulletin about a quake that actually happened in 1925.) Science journalists who think their subjects are too complicated for AI treatment should think again, Mićo said: “AI could threaten our jobs and undermine independent critical science reporting, but it could also help enrich reporting and make our jobs easier if we design and apply them” with care.

For Caty Enders’s topic, “what neuroscience can teach us about telling true stories,” she drew on sources as diverse as the philosopher Daniel Dennett, who compared the self to a “bowerbird, gathering objects that delight it”; the Harvard scientist Joan Camprodon, who has called the brain “mind-bogglingly complex”; and the pioneering neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who said that while the “human mind is fundamentally incapable” of solving problems like the nature of consciousness, “we may proceed quite nicely without knowing the essence of things.” Caty’s three-part takeaway: “We need to confine ourselves to not overstating what we know. Ask good questions, learn to live with uncertainty. And bring those small, incremental, miraculous discoveries to life by telling their stories in a way that honors the human need for a good narrative.”

Kolawole Talabi took a winding path to his own takeaway: designing a board game to painlessly educate children and adults about the dangers facing the world’s shark population. At first tempted to study the environmental effects of livestock farming in Africa, he learned that the Boston-area academic complex had far more experts on marine science, from MIT and Harvard to Woods Hole and the New England Aquarium. So he decided to focus on sharks — the public’s irrational loathing for them (a product of the movie “Jaws”) and certain countries’ appetite for their fins. Then he considered doing a long article or a book proposal before finally settling on a game as the right vehicle for his mission. The stylishly designed Reef Raffle, one of three games he worked on, also has a kids’ version, Reef Ruffle. ’Wole is optimistic about finding a marketer.

On a 2016 visit to Cambridge, Ehsan Masood found himself at the Legal Sea Foods on Main Street, dining with a 90-year-old Harvard economist who’d been a source for his book “The Great Invention.” The economist, Gustav Papanek, had quite a back story: A child of parents who were noted European socialists, he became a casualty of the 1950s red scare when the State Department exiled him to a posting in Pakistan as part of the purge of anyone vaguely left-wing from its ranks. The story struck a nerve with Ehsan, who had barely heard of Senator Joe McCarthy or blacklists, and when he returned to Cambridge as a KSJ fellow, he resolved to find more academics like Papanek — before it was too late — and tell their stories in an audio documentary. And he found them — living and vibrant, if aging, “Voices From a Forgotten Generation” (to use the documentary’s title). The work in progress, from which Ehsan presented an eight-minute excerpt, holds haunting echoes for present generations.

“The human microbiome has become far less diverse than it once was, partly because of our diet and use of antibiotics and antimicrobial products,” said Caroline Winter. “And we’re just beginning to understand how this could affect everything from our skin health to mental problems.” To find out what’s being done to counter the trend, Caroline researched pre- and probiotics and spent the year learning about the MIT spinoff AOBiome, which sells spray-on bacteria and raised more than $40 million to conduct pharmaceutical trials testing the effects of its patented product on acne, eczema, hypertension, and allergies. Caroline’s second project for the year was producing her first child, a baby boy named Johannes, born May 20. Now that’s something to showcase!

Leave a Reply