At most colleges and universities, the semester break is just that: a chance to get out of town and decompress, preferably somewhere warm with something cool to drink. At MIT, for more than four decades, it has been something different — the Independent Activities Period, or IAP, in which members of the MIT community can offer free courses on the topics of their choice, from poetry to cooking to synthetic biology.

And now, science and the media. Four members of the KSJ Class of 2017-18 gave their own IAP session on January 16 and 17 — four lively and disparate talks to more than a dozen community members, from programs as diverse as astrophysics, bioengineering, urban studies, and MIT Portugal.

“Quite a few of us fellows have taught science journalism skills before,” said Mićo Tatalović, who organized the event, “and we each have deep knowledge of our own subspecialties. So the IAP sessions seemed like a great opportunity to give back to the MIT community. which has welcomed us here so openheartedly, and I was glad to see so many people sign up and attend.”

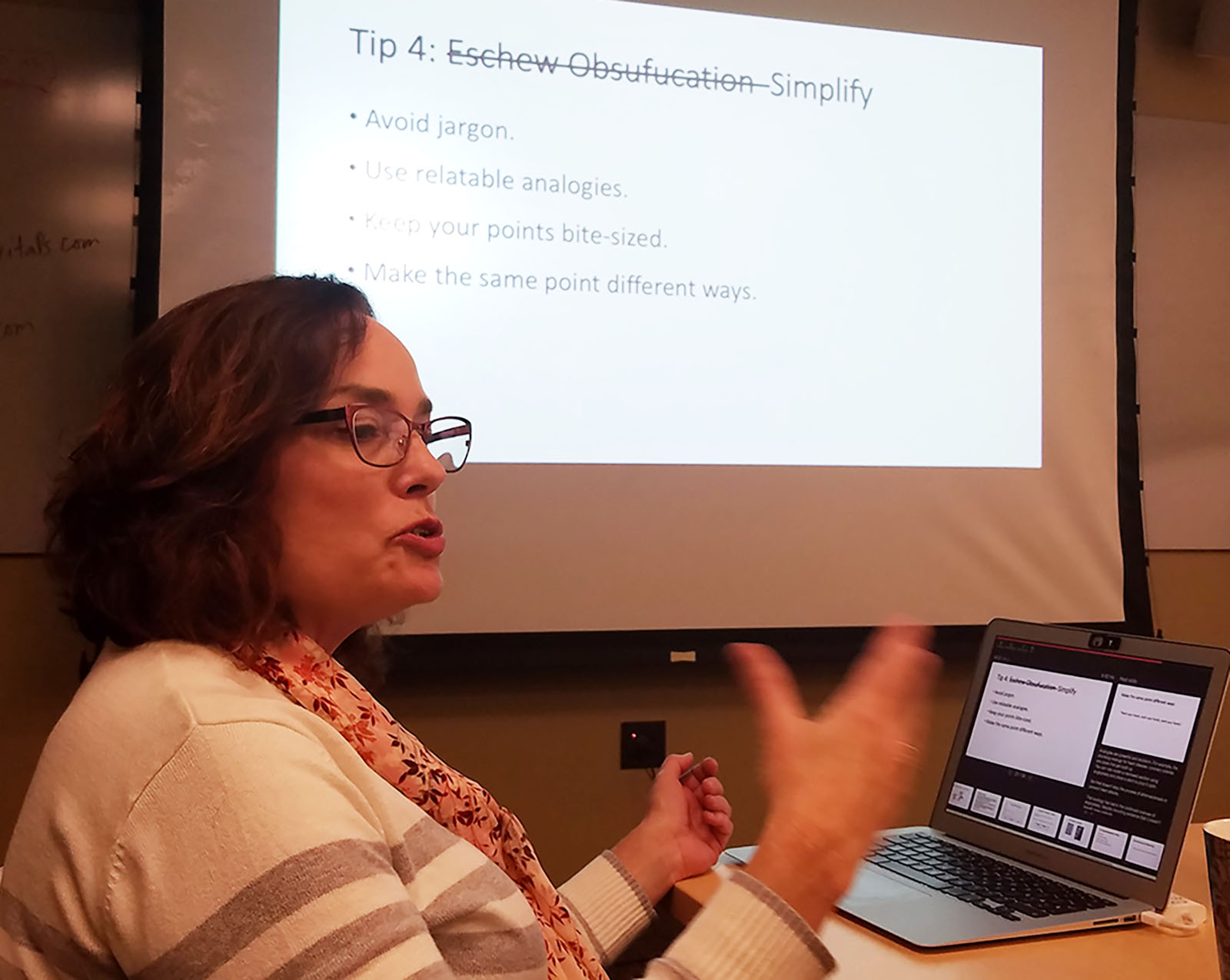

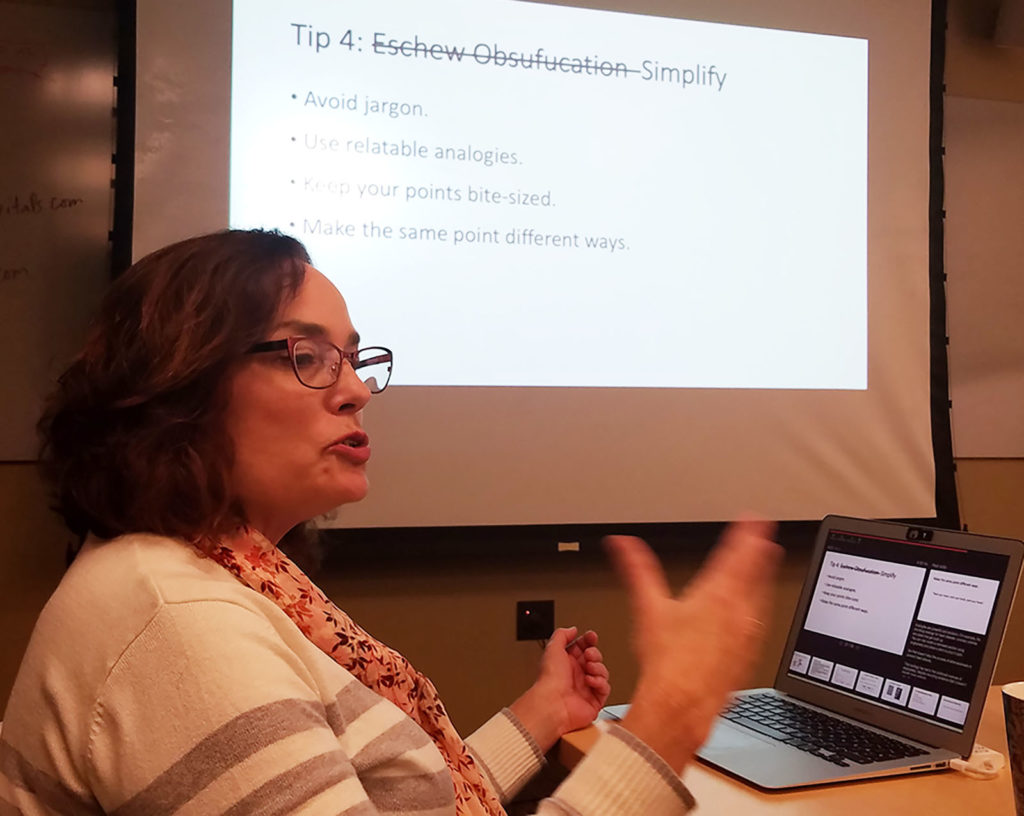

Teresa Carr, an award-winning investigative reporter with Consumer Reports, opened the event with a talk on five barriers to communicating science to a lay audience and how to overcome them — in particular, how to combat misinformation. Focus-group studies of health care communication show that using simple, jargon-free language to present evidence can be persuasive, Teresa said, but she acknowledged that may not be enough for politically charged topics like climate change. People dig in their heels to protect deeply held beliefs, and she highlighted research suggesting that telling people why and how they are being misled can make them more receptive to the facts.

Ehsan Masood, author of several books and editor of the London-based science policy magazine Research Fortnight, focused on the importance of narrative in science communication. Sometimes dismissed as a luxury, narrative writing can make complex discoveries and inventions come alive. Science ‘”is still an inherently human process,” Ehsan explained. “The process involves characters and plots; there is cooperation and competitiveness; years of tedium and moments of drama; truth and lies. In short, it has all the makings of good narrative.”

On Day 2, Joshua Hatch, assistant managing editor for data and interactives at The Chronicle of Higher Education and The Chronicle of Philanthropy, spoke about the dos and don’ts of information graphics, with a slideshow of great examples — and some spectacularly bad ones.

“Graphics should ultimately seek to tell a story,” he explained. “It need not be a heavily detailed or complex story, but the viewer should, at a glance, get a sense of what it is the graphic is saying. Smart and thoughtful decisions about color and text can help with that. So too can empowering viewers to compare data or see connections.”

And Mićo, who is news editor at New Scientist and chairman of the Association of British Science Writers, concluded the two-day event with a talk about science news — where it comes from, how to pitch stories to different publications, how to write news well, and how to attract online readers without compromising on quality.

The talk “was quite interactive,” he said, “with people asking questions and discussing issues as we went along, and finally brainstorming a headline for a hit story we had at New Scientist simulating a real-world newsroom experience.” (The actual headline, from New Scientist in January 2017, was “Chimps beat up, murder, and then cannibalize their former tyrant.”) More than half an hour after the session’s official closing time, audience members lingered to talk about these and other striking examples of the science journalist’s craft.

Leave a Reply