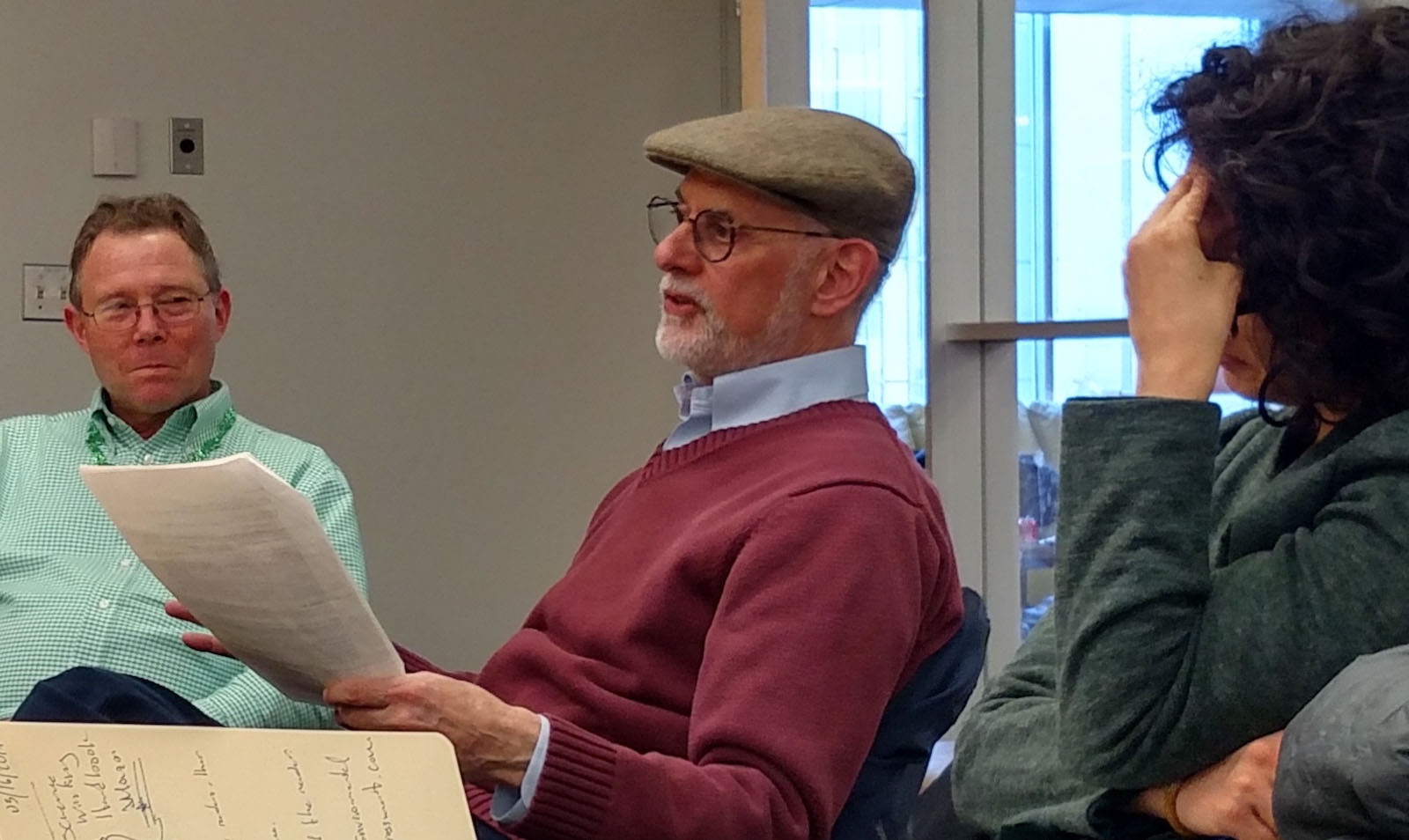

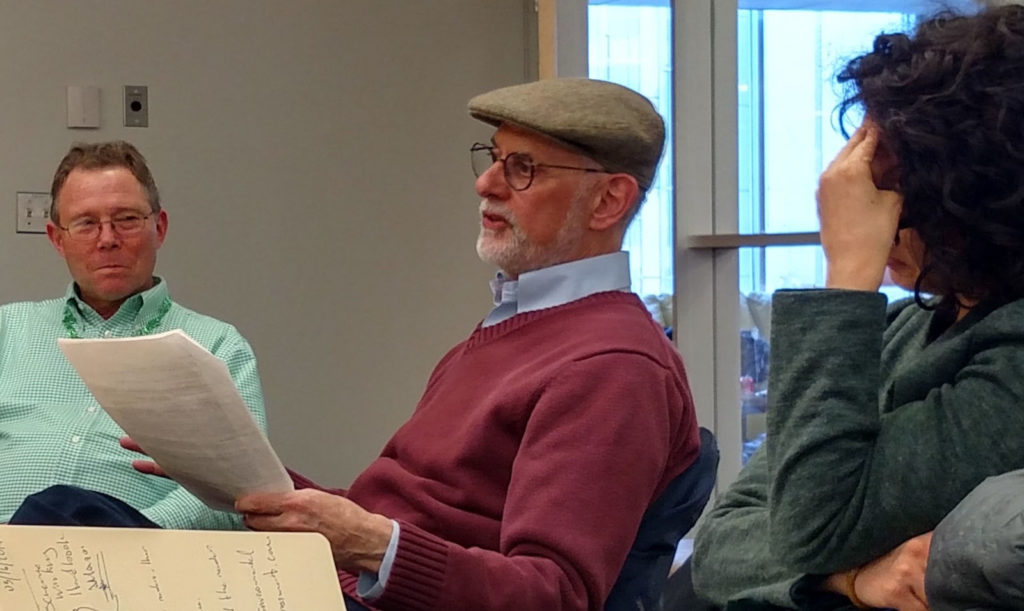

Decked out in a tweed jacket and a tweed flat cap to match, Mark Kramer arrived at his KSJ seminar looking the picture of a New England author. He doffed the jacket and traded the speaker’s usual spot up front for a seat in the middle of the table, creating an informal setting for his March 16 presentation on narrative journalism. Once the fellows and visitors finished their usual round of introductions, Kramer sat silent for a long moment. He scratched his beard thoughtfully.

“I’m a bit puzzled how to start,” he admitted. “I’m not primarily a science writer.” Kramer has authored several nonfiction books and co-edited the writer’s guide “Telling True Stories.” He’s currently professor of clinical practice in narrative journalism and writer in residence at Boston University’s journalism department. He also founded — and continues to direct — the annual Power of Narrative Conference.

Science writer or not, Kramer has given a lot of thought to the role that strong storytelling plays in science communication. “I’ve always seen science writing as a double helix,” he said, “with science explanation being one spiral and human relations being the other.” Narrative elements scaffold the “human relations” half of science writing.

One important aspect of narrative journalism is the “self” that guides readers through a story. A standard news article is “de-selfed” and conveys “a minimal citizen sensibility,” Kramer said. In narrative journalism, on the other hand, a writer imbues the piece with enough humanity that she can engage her readers on difficult subjects.

“The voice you present does some magic alchemy with the reader,” Kramer said. It gives a writer the air of a courteous host, commanding the reader’s trust and respect. “This is the most powerful communicative tool you have,” Kramer told KSJ, because it can give a writer permission to discuss anything from government policy to the meaning of life.

To Kramer, the voice of narrative journalism should be witty and formal yet personal, as though the writer were telling a story at a dinner party among new friends. He contrasted this tone with the voice of academics, who allow themselves quirky jokes only in the titles of their papers before getting down to business in the text. (Striking the pose of a stuffy scholar, he crossed his arms and pulled a deep frown.) To cultivate this casual tone in his own work, Kramer finishes each day of field reporting by writing a letter about whatever happened that day and how he feels about it. More often than not, he said, these personable accounts become the backbone of his finished piece.

Another important facet of narrative journalism is what Kramer calls “the moving now” — a foreground narrative that the writer continually digresses from and returns to throughout the piece. This spliced-up story might describe just 10 or 15 minutes of cool, complex action amid days of routine reporting, Kramer said. But a clear, compelling “moving now” can hook readers and keep them on the line for an entire piece.

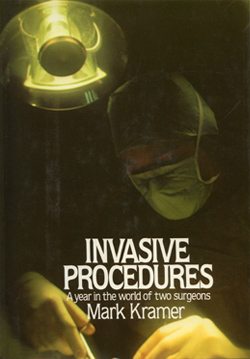

To foster a sense of immediacy in the “moving now,” Kramer emphasized the importance of scene setting. He recommended collecting sensory details in the field, as well as searching for instances of emotionality that don’t stem from the writer. Kramer drew an example from his 1983 book “Invasive Procedures: A Year in the World of Two Surgeons.” Although he himself had visceral responses to witnessing surgeries, he got more emotionally charged book material when a furious surgeon started yelling at a nurse because he hadn’t been assigned his usual operating room. “I’m writing, and I’m writing fast,” Kramer said, “[because] I’ve suddenly decoded the politics of the surgical staff.”

When asked what he tells interviewees who don’t end up being quoted in his stories, he replied, “Not my problem.” Writers should never feel beholden to their sources, he said; getting chummy with interviewees can undermine a writer’s camaraderie with the reader.

“As a longtime admirer of the BU Power of Narrative conference,” said KSJ fellow Meera Subramanian (herself the author of a narrative nonfiction book, “A River Runs Again”), “it was great to sit around the KSJ seminar table with Mark Kramer as he shared the seemingly tiny tips that really make narrative journalism work — in the field, in our notebooks, and on the page, right down to the use of the underused period.”

According to Kramer, narrative science communication is more important now than ever. “Suddenly, with the results of the last election,” he said, “we’re in a world emergency that has a lot to do with explaining science.” It’s no longer enough to simply write a digestible explanation of something like global warming and expect it to change hearts and minds: “It seems to me that the main show is in political discussion,” where narrative journalism can get writers a foot in the door of readers who might otherwise be unreachable.

I took Mark Kramer’s narrative writing class when he and I were colleagues, both of us profs at Boston University’s College of Communication. I was teaching journalism, mostly the day-to-day stuff that contained “minimum citizen sensibility,” as Mark calls it. His course was such an eye-opener for me that I took it twice, learning a lot of new stuff each time. I began incorporating his lessons into my courses, requiring at least one narrative piece from my grad students. Mark is a wonderful writer and a brilliant writing teacher, and his narrative writing conferences are inspirational.